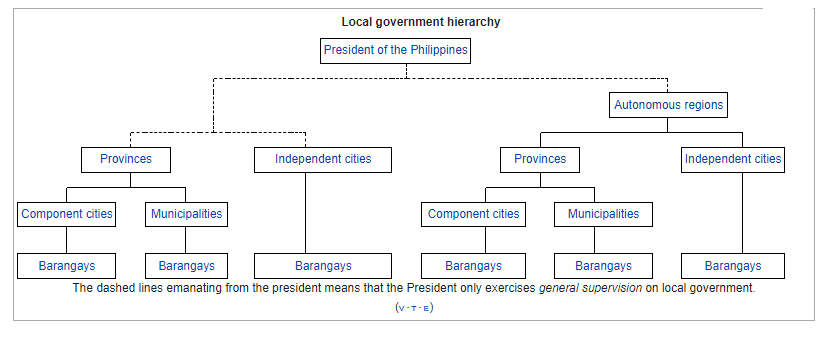

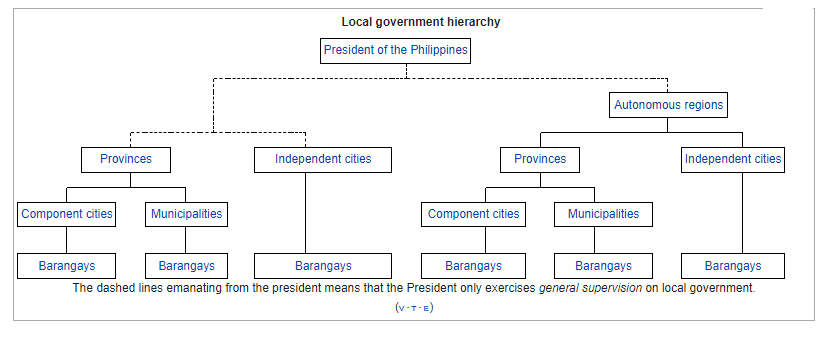

Provinces and independent cities are organized into national government regions but those are administrative regions and not separately governed areas with their own elected governments.

According to the Constitution of the Philippines, the local governments "shall enjoy local autonomy", and in which the Philippine president exercises "general supervision". Congress enacted the Local Government Code of the Philippines in 1991 to "provide for a more responsive and accountable local government structure instituted through a system of decentralization with effective mechanisms of recall, initiative, and referendum, allocate among the different local government units their powers, responsibilities, and resources, and provide for the qualifications, election, appointment and removal, term, salaries, powers and functions and duties of local officials, and all other matters relating to the organization and operation of local units." Local government units are under the control and supervision of the Department of the Interior and Local Government.

Autonomous regions

Autonomous regions have more powers than other local governments. The constitution limits the creation of autonomous regions to Muslim Mindanao and the Cordilleras but only one autonomous region exists: the Bangsamoro, which replaced the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). In 1989, a plebiscite established the ARMM. In 2001, a plebiscite in the ARMM confirmed the previous composition of the autonomous region and added Basilan (except for the city of Isabela) and Marawi in Lanao del Sur. Isabela City remains a part of the province of Basilan despite rejecting inclusion in the ARMM. In 2019, another plebiscite confirmed the replacement of the ARMM with the Bangsamoro, and added Cotabato City and 63 barangays in Cotabato.

A Cordillera Autonomous Region has never been formed because two plebiscites, in 1990 and 1998, both resulted in just one province supporting autonomy; this led the Supreme Court ruling that autonomous regions should not be composed of just one province.

Each autonomous region has a unique form of government. The ARMM had a regional governor and a regional legislative assembly, mimicking the presidential system of the national government. The Bangsamoro will have a chief minister responsible to parliament, with parliament appointing a wa'lī, or a ceremonial governor, in a parliamentary system.

An autonomous region of the Philippines (Filipino: rehiyong awtonomo ng Pilipinas) is a first-level administrative division that has the authority to control a region's culture and economy. The Constitution of the Philippines allows for two autonomous regions: in the Cordilleras and in Muslim Mindanao. Currently, Bangsamoro, which largely consists of the Muslim-majority areas of Mindanao, is the only autonomous region in the country.

Current autonomous region

Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

On October 15, 2012, a preliminary agreement was signed by the Government of the Philippines' chief negotiator Marvic Leonen, MILF Peace Panel Chair Mohagher Iqbal and Malaysian facilitator Tengku Dato' Ab Ghafar Tengku Mohamed along with President Aquino, Prime Minister Najib Razak of Malaysia, MILF chairman Al-Hajj Murad Ebrahim and Secretary-General Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation at Malacañang Palace in Manila.

It replaced the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and was formed after voters decided to ratify the Republic Act no. 11054 or the Bangsamoro Organic Law in a January 21 plebiscite. The ratification was announced on January 25, 2019, by the Commission on Elections. This marked the beginning of the transition of the ARMM to the BARMM.

Former autonomous region

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) was proposed in 1976 during the Ferdinand Marcos administration and created on August 1, 1989, through Republic Act No. 6734 (otherwise known as the Organic Act) in pursuance with a constitutional mandate. In 2012 President Benigno Aquino III described ARMM as a "failed experiment". He proposed an autonomous region named Bangsamoro to replace ARMM with the agreement between the government and Moro Islamic Liberation Front.

A plebiscite was held in the provinces of Basilan, Cotabato, Davao del Norte, Davao Oriental, Davao del Sur, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Palawan, South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Zamboanga del Norte and Zamboanga del Sur; and in the cities of Cotabato, Davao, Dapitan, Dipolog, General Santos, Koronadal, Iligan, Marawi, Pagadian, Puerto Princesa and Zamboanga to determine if their residents wished to be part of the ARMM. Of these areas, only four provinces (Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi) voted in favor of inclusion in the new autonomous region. The ARMM was officially inaugurated on November 6, 1990, in Cotabato City, which was designated as its provisional capital.

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) ceased to exist after a two-part 2019 plebiscite that ratified the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL). It was replaced with the new Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) and now under the interim government, Bangsamoro Transition Authority.

Proposed autonomous regions

Cordilleras

Further information: Cordillera autonomy movement, 1990 Cordillera Autonomous Region creation plebiscite, and 1998 Cordillera Autonomous Region creation plebiscite

The Cordillera Administrative Region administers the area that was designated for an autonomous region. Two plebiscites were held in the Cordilleras, the latest in 1998, to create an autonomous region, but both failed. There have been bills filed in Congress to re-propose and establish an autonomous region in the Cordilleras, but none of these have succeeded.

In 1990, a plebiscite was held to create an autonomous region under Republic Act No. 6766 but only Ifugao voted in favor of the law's ratification. The component provinces of the Cordillera Administrative Region at the time and the city of Baguio participated in the plebiscite with only localities voting in favor of the law's ratification to be part of a new autonomous region in the Cordilleras. There was also a failed attempt to establish an autonomous region with a single province.

Metro Manila

It was proposed that the National Capital Region or Metro Manila be converted to an autonomous region. Metro Manila is governed by mayors of its 16 highly urbanized cities and 1 independent municipality with the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority serving as an advisory body to the local government units of the metropolis. Former Quezon City Mayor Herbert Bautista had advocated for a Metro Manila autonomous region as an alternative to President Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign for federalism, which would render Metro Manila as an independent state within the Philippines.

Provinces

Outside the lone autonomous region, the provinces are the highest-level local government. The provinces are organized into component cities and municipalities. A province is governed by the governor and a legislature known as the Sangguniang Panlalawigan.

In the Philippines, provinces (Filipino: lalawigan) are one of its primary political and administrative divisions. There are 81 provinces at present, which are further subdivided into component cities and municipalities. The local government units in the National Capital Region, as well as independent cities, are independent of any provincial government. Each province is governed by an elected legislature called the Sangguniang Panlalawigan and an elected governor.

The provinces are grouped into seventeen regions based on geographical, cultural, and ethnological characteristics. Thirteen of these regions are numerically designated from north to south, while the National Capital Region, the Cordillera Administrative Region, the Southwestern Tagalog Region, and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao are only designated by acronyms.

Each province is a member of the League of Provinces of the Philippines, an organization which aims to address issues affecting provincial and metropolitan government administrations.

Government

A provincial government is autonomous of other provinces within the Republic. Each province is governed by two main elected branches of the government: executive and legislative. Judicial affairs are separated from provincial governance and are administered by the Supreme Court of the Philippines. Each province has at least one branch of a Regional Trial Court.

Executive

The provincial governor is chief executive and head of each province. Elected to a term of three years and limited to three consecutive terms, he or she appoints the directors of each provincial department which include the office of administration, engineering office, information office, legal office, and treasury office.

Legislative

The vice governor acts as the president for each Sangguniang Panlalawigan (SP; "Provincial Board"), the province's legislative body. Every SP is composed of regularly elected members from provincial districts, as well as ex officio members. The number of regularly elected SP members allotted to each province is determined by its income class. First- and second-class provinces are provided ten regular SP members; third- and fourth-class provinces have eight, while fifth- and sixth-class provinces have six. Exceptions are provinces with more than five congressional districts, such as Cavite with 16 regularly elected SP members, and Cebu, Negros Occidental and Pangasinan which have twelve each.

Every SP has designated seats for ex officio members, given to the respective local presidents of the Association of Barangay Captains (ABC), Philippine Councilors' League (PCL), and Sangguniang Kabataan (SK; "Youth Council").

The vice governor and regular members of an SP are elected by the voters within the province. Ex officio members are elected by members of their respective organisations.

Relation to other levels of government

National government

National intrusion into the affairs of each provincial government is limited by the Philippine Constitution. The President of the Philippines however coordinates with provincial administrators through the Department of the Interior and Local Government. For purposes of national representation, each province is guaranteed its own congressional district. One congressional representative represents each district in the House of Representatives. Senatorial representation is elected at an at-large basis and not apportioned through territory-based districts.

Cities and municipalities

Those classified as either "highly urbanized" or "independent component" cities are independent from the province, as provided for in Section 29 of the Local Government Code of 1991. Although such a city is a self-governing second-level entity, in many cases it is often presented as part of the province in which it is geographically located, or in the case of Zamboanga City, the province it last formed part the congressional representation of.

Local government units classified as "component" cities and municipalities are under the jurisdiction of the provincial government. In order to make sure that all component city or municipal governments act within the scope of their prescribed powers and functions, the Local Government Code mandates the provincial governor to review executive orders issued by mayors, and the Sangguniang Panlalawigan to review legislation by the Sangguniang Panlungsod (City Council) or Sangguniang Bayan (Municipal Council), of all component cities and municipalities under the province's jurisdiction.

Barangays

The provincial government does not have direct relations with individual barangays. Supervision over a barangay government is the mandate of the mayor and the Sanggunian of the component city or municipality of which the barangay in question is a part.

Classification

Provinces based on income classification.

Provinces are classified according to average annual income based on the previous 4 calendar years. Effective July 29, 2008, the thresholds for the income classes for cities are:

A province's income class determines the size of the membership of its Sangguniang Panlalawigan, and also how much it can spend on certain items, or procure through certain means.

Cities and municipalities

Municipal government in the Philippines is divided into three – independent cities, component cities, and municipalities (sometimes referred to as towns). Several cities across the country are "independent cities" which means that they are not governed by a province, even though like Iloilo City the provincial capitol might be in the city. Independent city residents do not vote for nor hold provincial offices. Far more cities are component cities and are a part of a province. Municipalities are always a part of a province except for Pateros which was separated from Rizal to form Metro Manila.

Cities and municipalities are governed by mayors and legislatures, which are called the Sangguniang Panlungsod in cities and the Sangguniang Bayan in municipalities.

A city (Filipino: lungsod/siyudad) is one of the units of local government in the Philippines. All Philippine cities are chartered cities (Filipino: nakakartang lungsod), whose existence as corporate and administrative entities is governed by their own specific municipal charters in addition to the Local Government Code of 1991, which specifies their administrative structure and powers. As of September 7, 2019, there are 146 cities.

A city is entitled to at least one representative in the House of Representatives if its population reaches 250,000. Cities are allowed to use a common seal. As corporate entities, cities have the power to take, purchase, receive, hold, lease, convey, and dispose of real and personal property for its general interests, condemn private property for public use (eminent domain), contract and be contracted with, sue and exercise all the powers conferred to it by Congress. Only an Act of Congress can create or amend a city charter, and with this city charter Congress confers on a city certain powers that regular municipalities or even other cities may not have.

Despite the differences in the powers accorded to each city, all cities regardless of status are given a bigger share of the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) compared to regular municipalities, as well as being generally more autonomous than regular municipalities.

Government

A city's local government is headed by a mayor elected by popular vote. The vice mayor serves as the presiding officer of the Sangguniang Panlungsod (city council), which serves as the city's legislative body. Upon receiving their charters, cities also receive a full complement of executive departments to better serve their constituents. Some departments are established on a case-by-case basis, depending on the needs of the city.

Offices and officials common to all cities

| Office | Head | Mandatory / Optional |

|---|

| City Government |

Mayor |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Sangguniang Panlungsod |

Vice Mayor as presiding officer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office of the Secretary to the Sanggunian |

Secretary to the Sanggunian |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Treasury Office |

Treasurer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Assessor's Office |

Assessor |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Accounting and Internal Audit Services |

Accountant |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Budget Office |

Budget Officer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Planning and Development Office |

Planning and Development Coordinator |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Engineering Office |

Engineer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Health Office |

Health Officer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office of Civil Registry |

Civil Registrar |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office of the Administrator |

Administrator |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office of Legal Services |

Legal Officer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office on Social Welfare and Development Services |

Social Welfare and Development Officer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office on General Services |

General Services Officer |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office for Veterinary Services |

Veterinarian |

Mandatory |

|---|

| Office on Architectural Planning and Design |

Architect |

Optional |

|---|

| Office on Public Information |

Information Officer |

Optional |

|---|

| Office for the Development of Cooperatives |

Cooperative Officer |

Optional |

|---|

| Office on Population Development |

Population Officer |

Optional |

|---|

| Office on Environment and Natural Resources |

Environment and Natural Resources Office |

Optional |

|---|

| Office of Agricultural Services |

Agriculturist |

Optional |

|---|

Source: Local Government Code of 1991

Subdivisions

Cities, like municipalities, are composed of barangays (Brgy), which can range from urban neighborhoods (such as Barangay 9, Santa Angela in Laoag), to rural communities (such as Barangay Iwahig in Puerto Princesa). Barangays are sometimes grouped into officially defined administrative (geographical) districts. Examples of such are the cities of Manila (16 districts), Davao (11 districts), Iloilo (seven districts), and Samal (three districts: Babak, Kaputian and Peñaplata). Some cities such as Caloocan, Manila and Pasay even have an intermediate level between the district and barangay levels, called a zone. However, geographic districts and zones are not political units; there are no elected city government officials in these city-specific administrative levels. Rather they only serve to make city planning, statistics-gathering other administrative tasks easier and more convenient.

Classification

Income classification

Cities are classified according to average annual income of the city based on the previous four calendar years. Effective July 28, 2008, the thresholds for the income classes for cities are:

| Class | Average annual income

(₱ million) |

|---|

| First |

At least 500 |

|---|

| Second |

320+ but < 500 |

|---|

| Third |

240+ but < 320 |

|---|

| Fourth |

160+ but < 240 |

|---|

| Fifth |

80+ but < 160 |

|---|

| Sixth |

< 80 |

|---|

Legal classification

The Local Government Code of 1991 (Republic Act No. 7160) classifies all cities into one of three legal categories:

- Highly urbanized cities (HUC): Cities with a minimum population of two hundred thousand (200,000) inhabitants, as certified by the Philippine Statistics Authority, and with the latest annual income of at least fifty million pesos (₱50,000,000 or USD 1,000,000) based on 1991 constant prices, as certified by the city treasurer.

- There are currently 33 highly urbanized cities in the Philippines, 16 of which are located in Metro Manila.

- Independent component cities (ICC): Cities of this type have charters that explicitly prohibit their residents from voting for provincial officials. All five of them are considered independent from the province in which they are geographically located: Cotabato, Dagupan, Naga (Camarines Sur), Ormoc, and Santiago.

- Component cities (CC): Cities which do not meet the preceding requirements are deemed part of the province in which they are geographically located. If a component city is located along the boundaries of two or more provinces, it shall be considered part of the province of which it used to be a municipality.

- All but five of the remaining cities are considered component cities.

Independent cities

There are 38 independent cities in the Philippines, all of which are classified as either "Highly urbanized" or "Independent component" cities. A city classified as such:

- does not have its Sangguniang Panlungsod legislation subject to review by any province's Sangguniang Panlalawigan;

- does not share tax revenue with any province; and

- is directly supervised by the President of the Philippines through the city government (given that the provincial government no longer exercises supervision over city officials), as stated in Section 29 of the Local Government Code.

Currently, there are only four independent cities in two classes that can still participate in the election of provincial officials (governor, vice governor, and Sangguniang Panlalawigan members):

- Cities declared highly urbanized between 1987 and 1992, whose charters (as amended) explicitly permitted residents to both vote and run for elective positions in the provincial government, and therefore allowed by Section 452-c of the Local Government Code to maintain these rights: Lucena (Quezon), Mandaue (Cebu);

- Independent component cities whose charters (as amended) only explicitly allow residents to run for provincial offices: Dagupan (Pangasinan) and Naga (Camarines Sur)

Registered voters of the cities of Cotabato, Ormoc, Santiago, as well as all other highly urbanized cities, including those to be converted or created in the future, cannot participate in provincial elections.

In addition to the eligibility of some independent cities to vote in provincial elections, a few other situations become sources of confusion regarding the complete autonomy of independent cities from provinces:

- Some independent cities still serve as the seat of government for the province in which they are geographically located: Bacolod (Negros Occidental), Cagayan de Oro (Misamis Oriental), Cebu City (Cebu), Iloilo City (Iloilo), Lucena (Quezon), Puerto Princesa (Palawan) and Tacloban (Leyte). In such cases, the provincial government, apart from already financing the maintenance of its properties such as provincial government buildings and offices, may also provide the government of the independent city with an annual budget (determined by the province at its discretion) to aid in relieving incidental costs incurred by the city such as road maintenance due to increased vehicular traffic in the vicinity of the provincial government complex.

- Some independent cities are still grouped with their former provinces for the purposes of representation in Congress. While 24 independent cities have their own representative(s) in Congress, some remain part of the congressional representation of the province to which they formerly belonged: Butuan, for example, is still part of the 1st Congressional District of Agusan del Norte. In cases like this, independent cities that do not vote for provincial officials are excluded from Sangguniang Panlalawigan (provincial council) districts, and the allotment of SP members is adjusted accordingly by COMELEC with proper consideration of population. For example, Agusan del Norte (being a third income-class province) is entitled to elect eight members to its Sangguniang Panlalawigan, and belongs to two congressional districts. The seats of the Sangguniang Panlalawigan are not evenly distributed (4–4) between the province's first and second congressional districts because its 1st Congressional district contains Butuan, an independent city which does not vote for provincial officials. Rather, the seats are distributed 1–7 to account for the small population of the province's 1st Sangguniang Panlalawigan district (consisting only of Las Nieves) and the bulk of the province's population being in the second district. On the other hand, the city of Lucena, which is eligible to vote for provincial officials, still forms part of the province of Quezon's 2nd Sangguniang Panlalawigan district, which is coterminous with the 2nd congressional district of Quezon.

- General lack of distinction for independent cities, for practical purposes: Many government agencies, as well as Philippine society in general, still continue to classify many independent cities outside Metro Manila as part of provinces due to historical and cultural ties, especially if these cities were once or currently socio-economic and cultural capitals of the provinces to which they once belonged. Furthermore, most maps of the Philippines showing provincial boundaries almost never separate independent cities from the provinces in which they are geographically located, for cartographic convenience. Despite being first-level administrative divisions (i.e., on the same level as provinces, as stated in Section 25 of the LGC), independent cities are still treated by many to be on the same level as municipalities and component cities (second-level administrative divisions) for educational convenience and simplicity.

A component city, while enjoying relative autonomy on some matters compared to a regular municipality, is still considered part of a province. However, there are several sources of confusion:

- Some component cities form their own congressional representation, separate from their province. The representation of a city in the House of Representatives (or lack thereof) is not a criterion for independence from a province, as Congress is the national legislative body and is part of the national (central) government. Despite Antipolo, Biñan and San Jose del Monte having their own representatives in Congress, they are still component cities of Rizal, Laguna, and Bulacan, respectively, as their respective charters specifically converted them into component cities and have no provision stating a severance in relations with their respective provincial governments.

- Being part of an administrative region different from the province: Isabela City functions as a component city of Basilan: its tax revenues are shared with the provincial government, its residents are eligible to both vote and run for provincial offices, and it is served by the provincial government and the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of Basilan with regard to provincially devolved services. However, by opting out of joining the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), Isabela City's residents are ineligible to vote and run for regional offices of the Bangsamoro Parliament, unlike the rest of Basilan. Regional services provided to Isabela City come from offices in Region IX based in Pagadian; the rest of Basilan is serviced by the BARMM based in Cotabato City. Isabela City, while not independent from its province, is this outside the jurisdiction of the BARMM, the region to which the rest of Basilan belongs. Regions are not the primary subnational administrative divisions of the Philippines, but rather the provinces.

Creation of cities

Congress is the lone legislative entity that can incorporate cities. Provincial and municipal councils can pass resolutions indicating a desire to have a certain area (usually an already-existing municipality or a cluster of barangays) declared a city after the requirements for becoming a city are met. As per Republic Act No. 9009, these requirements include:

- locally generated income of at least ₱100 million (based on constant prices in the year 2000) for the last two consecutive years, as certified by the Department of Finance, AND

- a population of at least 150,000, as certified by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA); OR a contiguous territory of 100 square kilometers, as certified by the Land Management Bureau, with contiguity not being a requisite for areas that are on two or more islands.

Members of Congress (usually the involving representative of the congressional district to which the proposed city belongs) then draft the legislation that will convert or create the city. After the bill passes through both the House of Representatives and the Senate and becomes an Act of Congress, the President signs the Act into law. If the Act goes unsigned after 30 days it still becomes law despite the absence of the President's signature.

The creation of cities before 1983 was solely at the discretion of the national legislature; there were no requirements for achieving 'city' status other than an approved city charter. No income, population or land area requirements had to be met in order to incorporate cities before Batas Pambansa Bilang 337 (Local Government Code of 1983) became law. This is what made it possible for several current cities such as Tangub or Canlaon to be conferred such a status despite their small population and locally generated income, which do not meet current standards. The relatively low income standard between 1992 and 2001 (which was ₱20 million) also allowed several municipalities, such as Sipalay and Muñoz, to become cities despite not being able to meet the current ₱100 million local income standard.

Before 1987, many cities were created without any plebiscites conducted for the residents to ratify the city charter, most notable of which were cities that were incorporated during the early American colonial period (Manila and Baguio), and during the Commonwealth Era (1935–1946) such as Cavite City, Dansalan (now Marawi), Iloilo City, Bacolod, San Pablo and Zamboanga City. Only since 1987 has it been mandated under the Constitution that any change to the legal status of any local government unit requires the ratification by the residents that would be affected by such changes. Therefore, all cities created after 1987 – after meeting the requirements for cityhood as laid out in the Local Government Code of 1991 and Republic Act No. 9009 of 2001 – only acquired their corporate status after the majority of their voting residents approved their respective charters.

Motivations for cityhood

Although some early cities were given charters because of their advantageous (Baguio, Tagaytay) or strategic (Angeles City and Olongapo, Cotabato, Zamboanga) locations or in order to especially establish new government centers in otherwise sparsely populated areas (Palayan, Trece Martires, Quezon City), most Philippine cities were originally incorporated to provide a form of localized civil government to an area that is primarily urban, which, due to its compact nature and different demography and local economy, cannot be necessarily handled more efficiently by more rural-oriented provincial and municipal governments. However, not all cities are purely areas of dense urban settlement. To date there are still cities with huge expanses of rural or wilderness areas and considerable non-urban populations, such as Calbayog, Davao, Puerto Princesa and Zamboanga as they were deliberately incorporated with increased future resource needs and urban expansion, as well as strategic considerations, in mind.

With the enactment of the 1991 Local Government Code, municipalities and cities have both become more empowered to deal with local issues. Regular municipalities now share many of the same powers and responsibilities as chartered cities, but its citizens and/or leaders may feel that it might be to their best interest to get a larger share of internal revenue allotment (IRA) and acquire additional powers by becoming a city, especially if the population has greatly increased and local economy has become more robust. On the other hand, due to the higher property taxes that would be imposed after cityhood, many citizens have become wary of their town's conversion into a city, even if the municipality had already achieved a high degree of urbanization and has an annual income that already exceeds that of many existing lower-income cities. This has been among the cases made against the cityhood bids of many high-income and populous municipalities surrounding Metro Manila, most notably Bacoor and Dasmariñas (which finally became cities in June 2012 and November 2009 respectively), which for many years have been more qualified to become cities than others.

In response to the rapid increase in the number of municipalities being converted into cities since the enactment of the Local Government Code in 1991, Senator Aquilino Pimentel authored what became Republic Act No. 9009 in June 2001 which sought to establish a more appropriate benchmark by which municipalities that wished to become cities were to be measured.The income requirement was increased sharply from ₱20 million to ₱100 million in a bid to curb the spate of conversions into cities of municipalities that were perceived to have not become urbanized or economically developed enough to be able to properly function as a city.

Despite the passage of RA 9009, 16 municipalities not meeting the required locally generated income were converted into cities in 2007 by seeking exemption from the income requirement. This led to vocal opposition from the League of Cities of the Philippines against the cityhood of these municipalities, with the League arguing that by letting these municipalities become cities, Congress will set "a dangerous precedent" that would not prevent others from seeking the same "special treatment". More importantly, the LCP argued that with the recent surge in the conversion of towns that did not meet the requirements set by RA 9009 for becoming cities, the allocation received by existing cities would only drastically decrease because more cities will have to share the amount allotted by the national government, which is equal to 23% of the IRA, which in turn is 40% of all the revenues collected by the Bureau of Internal Revenue. The resulting legal battles resulted in the nullification of the city charters of the 16 municipalities by the Supreme Court in August 2010.

A municipality (Tagalog: bayan/munisipalidad; Hiligaynon: banwa; Cebuano: lungsod/munisipalidad; Pangasinan: baley; Kapampangan: balen/balayan; Central Bikol: banwaan; Waray: bungto/munisipyo; Ilocano: ili) is a local government unit (LGU) in the Philippines. It is distinct from city, which is a different category of local government unit. Provinces of the Philippines are divided into cities and municipalities, which in turn, are divided into barangays (formerly barrios) – villages. As of 7 September 2019, there are 1,488 municipalities across the country.

A municipality is the official term for, and the official local equivalent of, a town, the latter being its archaic term and in all of its literal local translations including Filipino. Both terms are interchangeable.

A municipal district is a now-defunct local government unit; previously certain areas were created first as municipal districts before they were converted into municipalities.

History

The era of the formation of municipalities in the Philippines started during the Spanish rule, in which the colonial government founded hundreds of towns and villages across the archipelago modeled after towns and villages in Spain. They were then grouped together along with a centralized town center called cabecera or poblacion where the ayuntamiento, or town hall, was located; the poblacion served as the nucleus of each municipality. Only the communities that were permanently settled under the reduccion system, and have fully converted into Catholicism, are allowed to form municipalities, while others that have not yet been fully converted are to be subdued until conditions permitted for them to be incorporated as municipalities. As time passed, municipalities were created out of already existing ones, leading to them becoming smaller in area over time. Each municipality was governed by a capitan, usually a member of native principalia of the town, who have the task of remitting revenues to the central government in Manila. Ever since its inception to the present day, the term "municipality" holds the same definition as "town" when the first towns grew in size under the Spanish pueblo system (pueblo meaning "town" in Spanish language) to be granted municipal charters, hence the current official term for such type of settlements.

During the American administration, the municipal system put in place by the preceding Spanish authorities was preserved and at the same time reformed with greater inclusiveness among all Filipinos. Municipal districts, which were in essence unincorporated areas presided over by local tribal chiefs set up by American authorities, were created for the first time in 1914. More municipalities were created during this time, especially in Mindanao where there was a massive influx of settlers from the Luzon and the Visayas. After a while the independent Republic of the Philippines was declared in 1946, all municipal districts were dissolved and were absorbed into or broken into municipalities. The latest guidelines in the creation of new municipalities were introduced in 1991 with the issuance of the Local Government Code.

Responsibilities and powers

Municipalities have some autonomy from the National Government of the Republic of the Philippines under the Local Government Code of 1991. They have been granted corporate personality enabling them to enact local policies and laws, enforce them, and govern their jurisdictions. They can enter into contracts and other transactions through their elected and appointed officials and can tax. They are tasked with enforcing all laws, whether local or national. The National Government assists and supervises the local government to make sure that they do not violate national law. Local Governments have their own executive and legislative branches and the checks and balances between these two major branches, along with their separation, are more pronounced than that of the national government. The Judicial Branch of the Republic of the Philippines also caters to the needs of local government units. Local governments, such as a municipalities, do not have their own judicial branch: their judiciary is the same as that of the national government.

Organization

According to Chapter II, Title II, Book III of Republic Act 7160 or the Local Government Code of 1991, a municipality shall mainly have a mayor (alkalde), a vice mayor (ikalawang alkalde / bise alkalde) and members (kagawad) of the legislative branch Sangguniang Bayan alongside a secretary to the said legislature.

The following positions are also required for all municipalities across the Philippines:

- Treasurer

- Assessor

- Accountant

- Budget Officer

- Planning and Development Coordinator

- Engineer / Building Official

- Health Officer

- Civil Registrar

- Municipal Disaster Risks Reduction and Management Officer

Depending on the need to do so, the municipal mayor may also appoint the following municipal positions:

- Administrator

- Legal Officer

- Agriculturist

- Architect

- Information Officer

- Tourism Officer

- Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Officer

- Municipal Social Welfare and Development Officer

Duties and functions

As mentioned in Title II, Book III of Republic Act 7160, the municipal mayor is the chief executive officer of the municipal government and shall determine guidelines on local policies and direct formulation of development plans. These responsibilities shall be under approval of the Sangguniang Bayan.

The vice mayor (bise-alkalde) shall sign all warrants drawn on the municipal treasury. Being presiding officer of the Sangguniang Bayan (English: Municipal Council), he can as well appoint members of the municipal legislature except its twelve (12) regular members or kagawad who are also elected every local election alongside the municipal mayor and vice mayor. In circumstances where the mayor permanently or temporarily vacates the position, he shall assume executive duties and functions.

While vice mayor presides over the legislature, he cannot vote unless the necessity of tie-breaking arises. Laws or ordinances proposed by the Sangguniang Bayan, however, may be approved or vetoed by the mayor. If approved, they become local ordinances. If the mayor neither vetoes nor approves the proposal of the Sangguniang Bayan for ten (10) days from the time of receipt, the proposal becomes law as if it had been signed. If vetoed, the draft is sent back to the Sangguniang Bayan. The latter may override the mayor by a vote of at least two-thirds (2 / 3) of all its members, in which case, the proposal becomes law.

A municipality, upon reaching a certain requirements – minimum population size, and minimum annual revenue – may opt to become a city. First, a bill must be passed in Congress, then signed into law by the President and then the residents would vote in the succeeding plebiscite to accept or reject cityhood. One benefit in being a city is that the city government gets more budget, but taxes are much higher than in municipalities.

Income classification

Municipalities are divided into income classes according to their average annual income during the previous four calendar years:

| Class | Average annual income ₱ |

|---|

| First |

At least 15,000,000 |

| Second |

10,000,000 – 14,999,000 |

| Third |

5,000,000 – 9,999,000 |

| Fourth |

3,000,000 – 4,999,000 |

| Fifth |

1,000,000 – 2,999,000 |

| Sixth |

At most 999,000 |

Barangays

Every city and municipality in the Philippines is divided into barangays, the smallest of the local government units. Barangays can be further divided into sitios and puroks but those divisions do not have leaders elected in formal elections supervised by the national government.

A barangay's executive is the Punong Barangay or barangay captain and its legislature is the Sangguniang Barangay, composed of barangay captain, the Barangay Kagawads (barangay councilors) and the SK chairman. The SK chairman also leads a separate assembly for youth, the Sangguniang Kabataan or SK.

A barangay (; abbreviated as Brgy. or Bgy.), historically referred to as barrio (abbreviated as Bo.), is the smallest administrative division in the Philippines and is the native Filipino term for a village, district, or ward. In metropolitan areas, the term often refers to an inner city neighborhood, a suburb, or a suburban neighborhood.[5] The word barangay originated from balangay, a type of boat used by a group of Austronesian peoples when they migrated to the Philippines.[6]

Municipalities and cities in the Philippines are subdivided into barangays, with the exception of the municipalities of Adams in Ilocos Norte and Kalayaan in Palawan, with each containing a single barangay. Barangays are sometimes informally subdivided into smaller areas called purok (English: "zone"), or barangay zones consisting of a cluster of houses for organizational purposes, and sitios, which are territorial enclaves—usually rural—far from the barangay center. As of March 2021, there are 42,046 barangays throughout the Philippines.

History

When the first Spaniards arrived in the Philippines in the 16th century, they found well-organized independent villages called barangays. The name barangay originated from balangay, a Malay word meaning "sailboat". Early Spanish dictionaries of Philippine languages make it clear that balangay was pronounced "ba-la-ngay", while today the modern barangay is pronounced "ba-rang-gay".

All citations regarding pre-colonial barangay lead to a single source, Juan de Plascencia's 1589 report Las costumbres de los indios Tagalos de Filipinas. However, historian Damon Woods challenges the concept of barangay as an indigenous political organization primarily due to lack of linguistic evidence. Based on indigenous language documents, Tagalogs did not use the word barangay to describe themselves or their communities. Instead, barangay is argued as a Spanish invention from an attempt by the Spaniards in reconstructing pre-conquest Tagalog society.

The first barangays started as relatively small communities of around 50 to 100 families. By the time of contact with Spaniards, many barangays have developed into large communities. The encomienda of 1604 shows that many affluent and powerful coastal barangays in Sulu, Butuan, Panay, Leyte and Cebu, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Pasig, Laguna, and Cagayan River were flourishing trading centers. Some of these barangays had large populations. In Panay, some barangays had 20,000 inhabitants; in Leyte (Baybay), 15,000 inhabitants; in Cebu, 3,500 residents; in Vitis (Pampanga), 7,000 inhabitants; Pangasinan, 4,000 residents. There were smaller barangays with fewer number of people. But these were generally inland communities; or if they were coastal, they were not located in areas which were good for business pursuits. These smaller barangays had around thirty to one hundred houses only, and the population varied from one hundred to five hundred persons. According to Legazpi, he founded communities with only twenty to thirty people.

Traditionally, the original "barangays" were coastal settlements of the migration of these Malayo-Polynesian people (who came to the archipelago) from other places in Southeast Asia (see chiefdom). Most of the ancient barangays were coastal or riverine. This is because most of the people were relying on fishing for their supply of protein and their livelihood. They also traveled mostly by water up and down rivers, and along the coasts. Trails always followed river systems, which were also a major source of water for bathing, washing, and drinking.

The coastal barangays were more accessible to trade with foreigners. These were ideal places for economic activity to develop. Business with traders from other countries also meant contact with other cultures and civilizations, such as those of Japan, Han Chinese, Indian people, and Arab people. These coastal communities acquired more cosmopolitan cultures, with developed social structures (sovereign principalities), ruled by established royalties and nobilities.

During the Spanish rule, through a resettlement policy called the Reducción, smaller scattered barangays were consolidated (and thus, "reduced") to form compact towns. Each barangay was headed by the cabeza de barangay (barangay chief), who formed part of the Principalía – the elite ruling class of the municipalities of the Spanish Philippines. This position was inherited from the first datus, and came to be known as such during the Spanish regime. The Spanish Monarch ruled each barangay through the Cabeza, who also collected taxes (called tribute) from the residents for the Spanish Crown.

When the Americans arrived, "slight changes in the structure of local government was effected". Later, Rural Councils with four councilors were created to assist, now renamed Barrio Lieutenant; it was later renamed Barrio Council, and then Barangay Council.

The Spanish term barrio (abbr. "Bo.") was used for much of the 20th century. Mayor Ramon Bagatsing of the City of Manila established the first Barangay Bureau in the Philippines, creating the blueprint for the barangay system as the basic socio-political unit for the city in the early 70s. This was quickly replicated by the national government, and in 1974 President Ferdinand Marcos ordered the renaming of barrios to barangays. The name survived the 1986 EDSA Revolution, though older people would still use the term barrio. The Municipal Council was abolished upon transfer of powers to the barangay system. Marcos used to call the barangay part of Philippine participatory democracy, and most of his writings involving the New Society praised the role of baranganic democracy in nation-building.

After the 1986 EDSA Revolution and the drafting of the 1987 Constitution, the Municipal Council was restored, making the barangay the smallest unit of Philippine government. The first barangay elections held under the new constitution was held on March 28, 1989, under Republic Act number 6679.

The last barangay elections were held in October 2013. Barangay elections scheduled in October 2017 were postponed following the signing of Republic Act number 10952. The postponement has been criticized by election watchdogs and in both the Philippine Congress and Senate. The Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting considers the postponement a move that would "only deny the people their rights to choose their leaders."

Organization

The modern barangay is headed by elected officials, the topmost being the Punong Barangay or the Barangay Chairperson (addressed as Kapitan; also known as the Barangay Captain). The Kapitan is aided by the Sangguniang Barangay (Barangay Council) whose members, called Barangay Kagawad ("Councilors"), are also elected.

The council is considered to be a local government unit (LGU), similar to the provincial and the municipal government. The officials that make up the council are the Punong Barangay, seven Barangay Councilors, and the chairman of Youth Council or Sangguniang Kabataan (SK). Thus, there are eight members of the Legislative Council in a barangay.

The council is in session for a new solution or a resolution of bill votes, and if the counsels and the SK are at tie decision, the barangay captain uses their vote. This only happens when the SK which is sometimes stopped and continued. In absence of an SK, the council votes for a nominated Barangay Council President, this president is not like the League of the Barangay councilors which composes of barangay captains of a municipality.

The Barangay Justice System or Katarungang Pambarangay is composed of members commonly known as Lupon Tagapamayapa (Justice of the peace). Their function is to conciliate and mediate disputes at the Barangay level to avoid legal action and relieve the courts of docket congestion.

Barangay elections are non-partisan and are typically hotly contested. Barangay captains are elected by first-past-the-post plurality (no runoff voting). Councilors are elected by plurality-at-large voting with the entire barangay as a single at-large district. Each voter can vote up to seven candidates for councilor, with the winners being the seven candidates with the most votes. Typically, a ticket usually consists of one candidate for Barangay Captain and seven candidates for the Councilors. Elections for the post of Punong Barangay and barangay kagawads are usually held every three years starting from 2007.

The barangay is often governed from its seat of local government, the barangay hall.

A tanod, or barangay police officer, is an unarmed watchman who fulfills policing functions within the barangay. The number of barangay tanods differs from one barangay to another; they help maintain law and order in the neighborhoods throughout the Philippines.

Funding for the barangay comes from their share of the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) with a portion of the allotment set aside for the Sangguniang Kabataan. The exact amount of money is determined by a formula combining the barangay's population and land area.

Local government hierarchy. The dashed lines emanating from the president means that the President only exercises general supervision on local government.

|

|

|

|

Total Local Government Units in the Philippines

Type

(English) | Filipino

equivalent | Head of

Administration | Filipino

equivalent | Number |

|---|

| Province |

Lalawigan/Probinsya |

Governor |

Gobernador |

81 |

| City |

Lungsod/Siyudad |

Mayor |

Punong Lungsod/Alkalde |

146 |

| Municipality |

Bayan/Munisipalidad |

Mayor |

Punongbayan/Alkalde |

1,488 |

| Barangay |

Barangay |

Barangay Chairman/Barangay Captain |

Punong-Barangay/Kapitan ng Barangay |

42,046 |

|